The Vietnam War is arguably one of the most politically divisive wars in American history. It inspired hundreds of films, television documentaries, novels, memoirs, and even songs. American involvement in the war continues to be debated, even today.

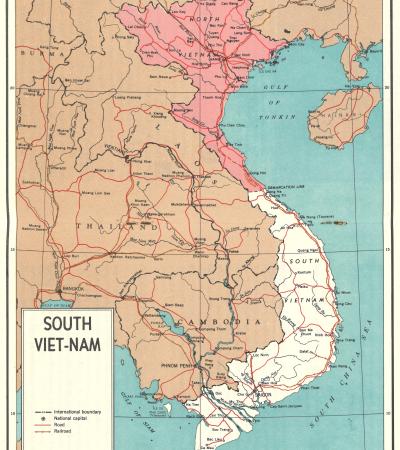

The participation of U.S. armed forces in Vietnam dates to the 1950s, when a few hundred military advisors were stationed in South Vietnam to advise the government and military on the use of American military equipment in the region. Following World War II, Vietnam had been divided into the communist Democratic Republic of Vietnam (also known as North Vietnam) and the non-communist Republic of Vietnam (also known as South Vietnam). North Vietnam received backing from China and the Soviet Union, while South Vietnam was backed by the U.S. and other anti-communist allies.

The Cold War was already underway, and the administration of American President Dwight D. Eisenhower was concerned about the spread of communism around the world. When war broke out between South Vietnam and North Vietnam in 1955, the United States government took notice. Many politicians of the time subscribed to a “domino theory,” which proposed that if one country in a region succumbed to communism, the surrounding countries would follow like dominoes, all falling to communism one after the other. The concern was that South Vietnam might lose its war with the North, putting other countries in East Asia at risk of communism.

By 1964, the number of American military advisors in South Vietnam had grown to 23,000. American advisors were assisting South Vietnamese battalions and were increasingly at risk of attack from the North Vietnamese and their guerilla allies in the South, known as the Viet Cong. Then American involvement in the conflict escalated when North Vietnamese boats allegedly attacked two U.S. Navy destroyers in the Gulf of Tonkin off the coast of Vietnam in August 1964. The second attack was later revealed to be based on misreported information, but both incidents were used to justify military escalation. The U.S. Congress passed a nearly unanimous resolution to give President Lyndon B. Johnson authority “to take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression” by the communist military of North Vietnam.

Less than a year later, in March of 1965, the Johnson administration launched a three-year bombing campaign in North Vietnam. Code named “Operation Rolling Thunder,” the massive effort was meant to disable the North Vietnamese forces that had been attacking the South. U.S. Marines landed on beaches near Da Nang, South Vietnam. The U.S. had officially entered the war.

Initially, support for American involvement in Vietnam was strong. After all, there was the “domino theory” and the Cold War to consider. U.S. Information Agency officers like Lloyd Burlingham worked throughout Southeast Asia to build support for American policies and counter communist propaganda. Politicians, including Wyoming Senator Gale McGee, argued that the U.S. Government must hold the line to stop communist expansion, even if that meant engaging in a war halfway across the globe.

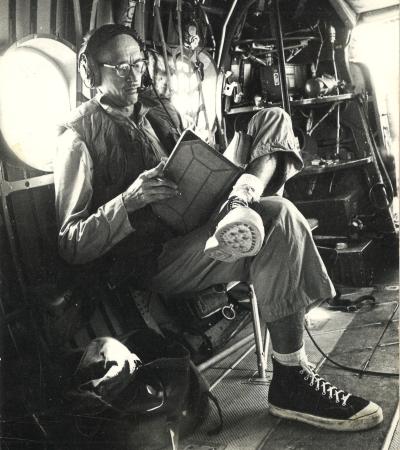

Nightly television news broadcasts kept American viewers informed about the war. Reporting from combat zones showed both the intensity and chaos of battle. This was the first time a war was televised, and as casualties mounted and were reported, public opinion began to change. War correspondents like Richard Tregaskis, who had covered World War II, provided firsthand accounts of American combat operations through works like Vietnam Diary (1963).

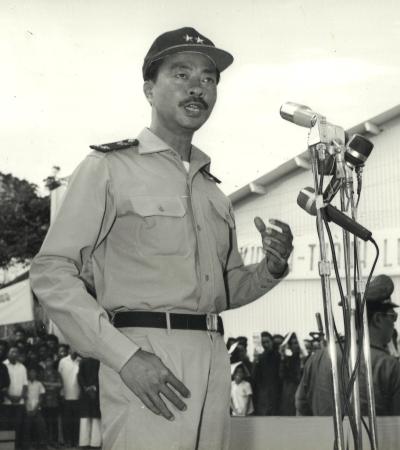

By 1968, according to a Gallup poll taken that year, only thirty-five percent of Americans approved of President Johnson’s handling of the war. Critical reporting by journalists like Stuart Loory exposed diplomatic efforts and military failures, contributing to growing public skepticism. More than 36,000 Americans had been killed and more than 100,000 had been wounded, and the North Vietnamese strategy of stubbornly outlasting the Americans seemed to be working. Battlefields were often jungles, swamps and mountainous areas where fighting was exacerbated by booby traps and ambushes. For the Americans, it was difficult to distinguish ally from enemy. The Viet Cong specialized in subterfuge and coordinated closely with North Vietnamese forces. Even reliable alliances proved challenging—leaders like South Vietnamese Prime Minister and later Vice President Nguyễn Cao Kỳ worked closely with U.S. forces, but the complex political situation made such partnerships difficult to maintain.

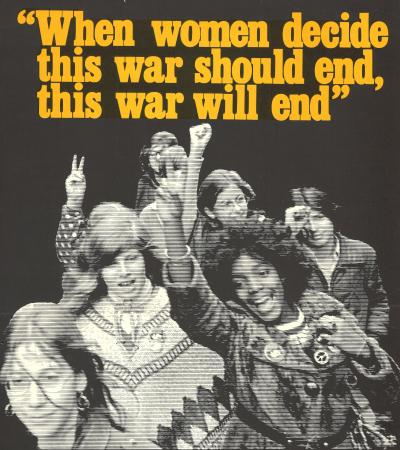

Back in the U.S., college campuses erupted with anti-war protests. As many as 50,000 American men fled to Canada to escape being drafted into the military. Journalist Roger Neville Williams was among those who fled to Canada and documented the experiences of war resisters. Some conscientious objectors set their draft cards on fire (a federal felony that came with a five-year prison sentence and a $10,000 fine). While there were those who felt that it was their patriotic duty to answer the governmental call to war, regardless of their feelings, many young men found ways around serving. College students were granted deferments, doctors were prevailed upon to grant medical exemptions and some enlisted in special National Guard units to avoid being sent to Vietnam. Those unlucky enough to get a low draft number shipped off to basic training and then on to the jungles, swamps, and mountainsides of Vietnam. Often, they were poor, less well educated and members of minority groups.

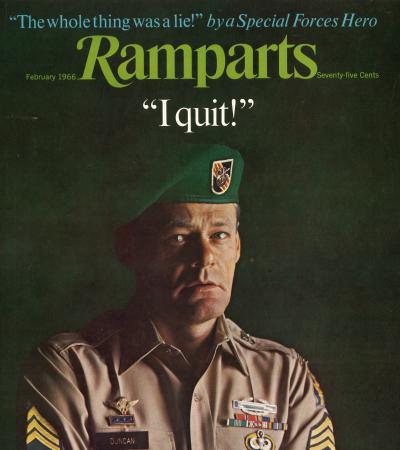

Veterans of the Vietnam War returned home to little fanfare and often outright animosity. Support for the war had not only dwindled but active and vocal opposition rocked the U.S. Veterans had to hide their identities on college campuses and in their communities. A few veterans joined groups like the Vietnam Veterans Against the War. Others, like Wyoming native James Mitchell Swan, expressed their disillusionment through personal letters, describing themselves as reluctant soldiers eager to see their service end.

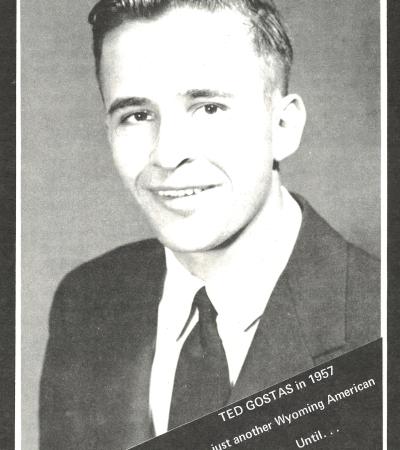

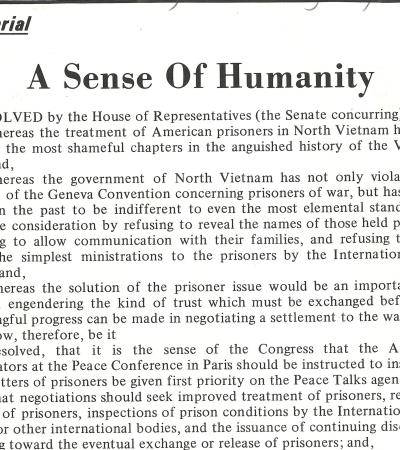

American involvement in the war ended in 1973, with the signing of the Paris Peace Accords. It was the first significant war ever to be lost by American forces. Military legal officers like Major General Lawrence Williams helped process the complex legal issues surrounding the war’s end, including the status of Vietnamese personnel who had worked with U.S. forces. Shortly thereafter, 591 American Prisoners of War (POWs) were repatriated to the U.S. Families like that of Wyoming’s Johanna Gostas, whose husband Major Theodore Gostas was held prisoner from 1968 to 1973, had organized campaigns to pressure for their release. But approximately 2,500 servicemen remained Missing in Action (MIA). The National League of POW/MIA Families was formed to provide support for military families and to pressure the American government to engage in recovering the remains of those killed in combat or while being held prisoner.

The war between North Vietnam and South Vietnam finally ended in 1975, when communist forces successfully captured Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam. In 1976, much to the delight of communist forces around the world, the north and south of the country were united as the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

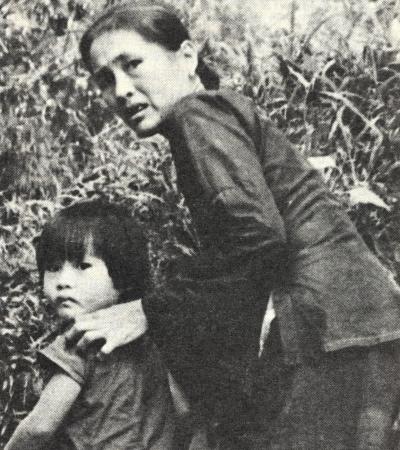

The human cost of the war was heartbreaking. A total of 58,220 Americans, including 119 Wyoming residents, had been killed and hundreds of thousands injured, both physically and psychologically. Millions of Vietnamese civilians were also killed. The political cost of the war to the U.S. was equally substantial. Abroad, American superiority as a worldwide defender of freedom and justice was called into question. And at home, anti-war protests had rocked the nation and permanently divided families and communities.

In hindsight, many of those who had supported the war, including Senator Gale McGee, came to recognize the futility of American involvement. The loss of the war left an indelible mark on the American psyche. The Vietnam War remains a gauge against which American military involvement in international conflict is measured today.