Journalist Stuart H. Loory (1932-2015) covered the Vietnam War as a White House correspondent for the Los Angeles Times (1967-1971), earning the Raymond Clapper Memorial Award in 1968 but also landing on President Nixon's “Enemies List” for his critical reporting. With colleague David Kraslow, he co-authored The Secret Search for Peace in Vietnam, exposing President Johnson’s diplomatic efforts to end the war. His papers include correspondence with high-ranking officials like Vice President Hubert Humphrey and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, research files for his Vietnam books, interview transcripts, photographs, and substantial documentation of military affairs and anti-war activities.

Additional content for this collection can be found in the "Inventory for collection."

CBS News Special Report, August 9, 1965

This transcript covers a CBS television broadcast interview with U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk and Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara. The discussion was focused on decisions made about the U.S. engagement in Vietnam. It provides insight into official government perspective on the Vietnam War as of August, 1965.

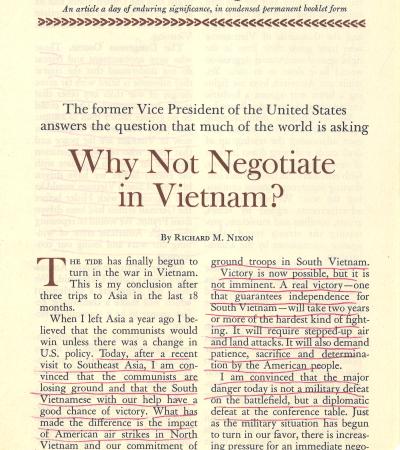

"Why Not Negotiate in Vietnam?" by Richard M. Nixon, The Reader's Digest, December, 1965

This article argues that negotiating peace in Vietnam too soon would be dangerous because it could make a communist victory look like a success. Nixon believed the U.S. should only negotiate when it was clear that North Vietnam could not win, and that America must stay strong to protect the independence of South Vietnam. At the time this article was written, Nixon, who had been Vice President, was not holding public office.

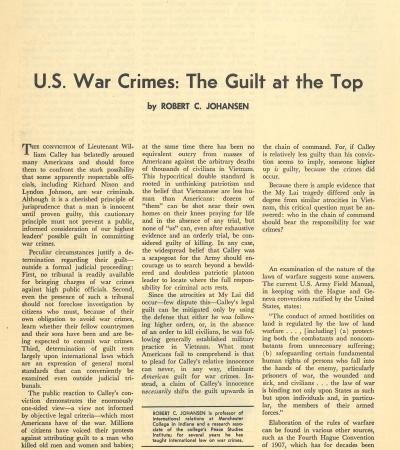

"U.S. War Crimes: The Guilt at the Top" by Robert C. Johansen, The Progressive, June, 1971

This article argues that responsibility for U.S. war crimes in Vietnam goes beyond individual soldiers and extends up the chain of command to top military and civilian leaders. It cites laws like the Geneva Conventions and evidence of widespread practices including bombing villages, creating “free-strike zones,” and mistreating civilians and prisoners, all of which high-ranking officials likely knew about. The author concludes that leaders including Presidents Johnson and Nixon, as well as top generals, may bear responsibility for these crimes.

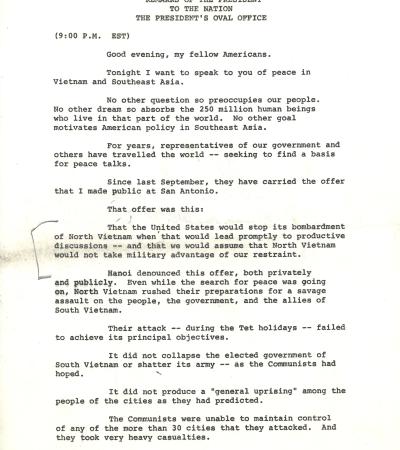

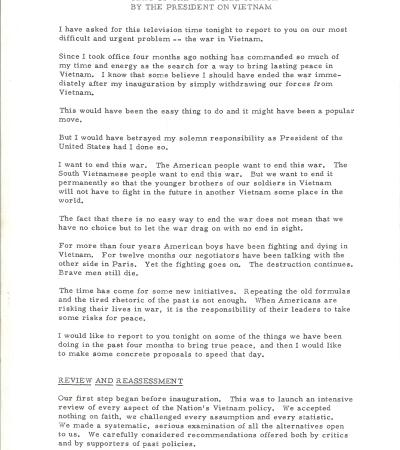

White House Press Release, March 31, 1968

This press release covers a speech delivered by President Lyndon B. Johnson regarding the Vietnam War. He announced that the U.S. would greatly reduce bombing in North Vietnam to encourage peace talks, while still helping South Vietnam defend itself. At the end, Johnson surprised the country by declaring he would not run for a second term as president.

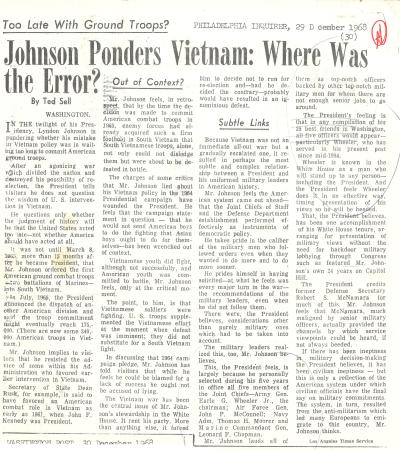

"Johnson Ponders Vietnam: Where Was The Error?" by Ted Sell, Philadelphia Inquirer, December 29, 1968

This article describes how President Lyndon Johnson, near the end of his time in office, reflected on whether his biggest mistake in Vietnam was waiting too long to send American combat troops. Johnson believed that by 1965, enemy forces were already too strong for South Vietnamese soldiers to handle alone, making U.S. involvement unavoidable.

White House Press Release, May 14, 1969

This press release covers the first major televised speech delivered by President Richard Nixon about the Vietnam War. It explains his plan for ending the Vietnam War responsibly. He rejects an immediate withdrawal or defeat, arguing instead for strengthening South Vietnamese forces and negotiating a fair peace that allows the people of South Vietnam to decide their own future.

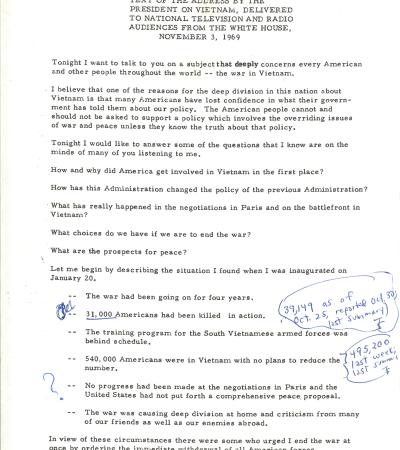

White House Press Release, November 3, 1969

This press release covers a speech delivered over radio and television by President Richard Nixon about the Vietnam War. Nixon explained that while he wanted peace, he would not order an immediate U.S. withdrawal because he believed it would harm America’s honor and security, instead promoting his plan of “Vietnamization,” where South Vietnamese forces would gradually take over the fighting.

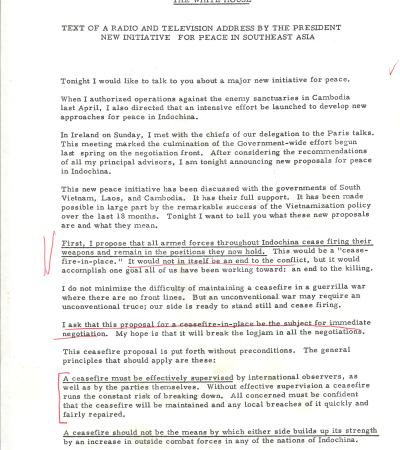

White House Press Release, October 7, 1970

This document is a press release covering a radio and television address by President Nixon. In it, he announced a new plan for peace in Southeast Asia. Nixon proposed a ceasefire across all of Indochina, an international peace conference, further troop withdrawals, political solutions for South Vietnam, and the immediate release of prisoners of war.

"The Secret Search For Peace In Vietnam" by David Kraslow and Stuart H. Loory, The Los Angeles Times, April, 1968

This reprint of a series of newspaper articles describes how U.S. and world leaders secretly tried to negotiate an end to the Vietnam War between 1965 and 1968. It describes how diplomats from European countries worked with U.S. officials to pass messages to North Vietnam, but bombing raids, miscommunication, and mistrust hampered the chance for peace. In the end, the articles assert that many opportunities for peace were missed because the U.S. government could not coordinate diplomacy and military action effectively.

"Our New GI: He Asks Why" by Georgie Anne Geyer, Chicago Daily News, January 13, 1969

This article discusses how American soldiers in the Vietnam War are different from those in past wars, showing more skepticism and independence rather than blind obedience. Many soldiers question why they are fighting and see themselves as professionals focused on technical skill rather than patriotism.

"Vietnam Casulaty Rates Dropped 37% After Cambodia Raid" by Benjamin F. Schemmer, Armed Forces Journal, January 18, 1971

This article explains that U.S. combat deaths in Vietnam dropped significantly in 1970, with overall casualty rates falling compared to earlier in the war. The South Vietnamese Army began taking on more fighting, and American medical care saved more lives, so soldiers’ chances of survival improved greatly. However, American pilots continued to face high risks, with aircraft losses remaining heavy and accounting for a growing share of combat deaths.

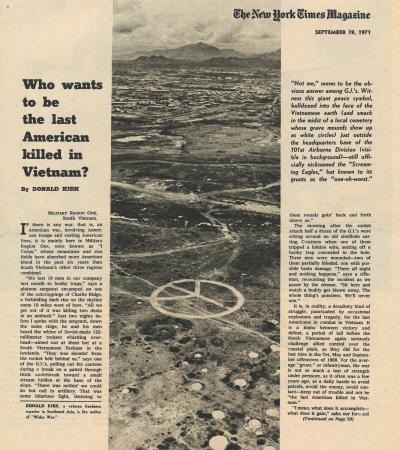

"Who Wants To Be The Last American Killed In Vietnam" by Donald Kirk, The New York Times Magazine, September 19, 1971

This article describes the experiences of the American soldiers still fighting in Vietnam as of 1971. Many U.S. troops felt the war had become pointless, with some openly saying they just wanted to avoid danger and not be “the last American killed in Vietnam”. Soldiers expressed frustration with leadership, growing drug use, racial tensions, and a sense that the war could not be won.

"Firebases Not Always Booming" by Charles W. Bishop, Army Times, November 3, 1971

This article explains that firebases in Vietnam were places where soldiers could rest, eat, and sleep between missions, but also where boredom often set in when there was no fighting. Soldiers filled the quiet time by reading, writing letters, playing cards, or repairing their gear, though many felt homesick and forgotten by people back home.

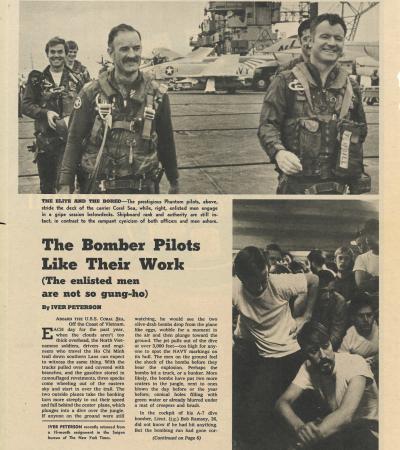

"The Bomber Pilots Like Their Work" by Iver Peterson, The New York Times Magazine, March 19, 1972

This article describes the experiences of U.S. Navy bomber pilots serving on aircraft carriers during the Vietnam War. The pilots enjoyed the excitement and challenge of flying, while many expressed little connection to the larger purpose of the war. Although officials said their bombing runs were effective, the pilots themselves often felt their missions made little difference.

"Militancy of Antiwar Veterans Is Rising" by Steven R. Weisman, The New York Times, July 16, 1972

This article covers the outspoken antiwar group Vietnam Veterans Against the War. The group, which often used dramatic protests like throwing away war medals or occupying symbolic sites, grew to thousands of members and demanded U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam and better rights for servicemen

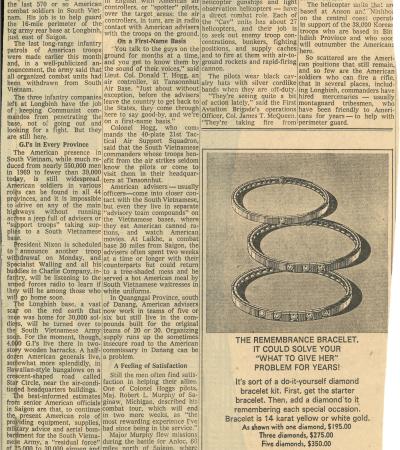

"All Over Vietnam, G.I.'s Still Have A Role" by Craig R. Whitney, August 27, 1972

This article explains that even though the number of American soldiers in Vietnam had dropped by 1972, many U.S. troops were still stationed there in support roles. Soldiers were spread across all provinces, helping train South Vietnamese forces, flying air missions, and keeping supply lines running.

"Pentagon Says Vietnam Arms Build-Up Is Mainly Over", The New York Times, November 21, 1972

This article explains that the Pentagon finished a big program to quickly send American weapons and supplies to South Vietnam before U.S. troops withdrew. In just three weeks, the U.S. delivered hundreds of planes, helicopters, tanks, and other military equipment to strengthen South Vietnam’s forces. Officials said the speed-up was to prepare for a possible cease-fire.

"Viet Wounds Are Cruelest of All U.S. Wars" by Rudy Abramson, The Washington Post, November 27, 1972

This article describes how the Vietnam War caused some of the most severe wounds of any U.S. war, leaving many soldiers permanently disabled from land mines, rockets, and booby traps. Thousands of veterans returned home missing limbs, paralyzed, or needing lifelong medical care, creating huge challenges for both them and the Veterans Administration.

"Sky Over North Vietnam" by George C. Wilson, The Washington Post, December 22, 1972

This article explains the dangerous battles between U.S. B-52 bombers and Soviet-made missiles fired by North Vietnam during the war. The B-52s, originally designed for Cold War nuclear missions, faced constant threats from SA-2 Guideline missiles and improved radar systems.The U.S. used new technologies like electronic countermeasures and drones to confuse enemy radar, but the missions still remained very risky for American B-52 crews.

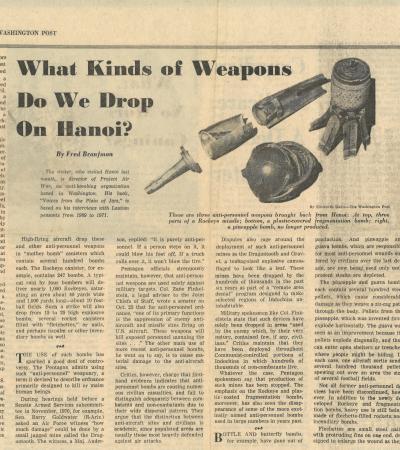

"What Kinds of Weapons Do We Drop On Hanoi?" by Fred Branfman, The Washington Post, December 24, 1972

This article details some of the types of weapons the U.S. dropped on North Vietnam during the Vietnam War, many of which were designed to injure rather than kill. It describes bombs like the Rockeye, fragmentation bombs, and even flechettes (tiny darts) that caused serious wounds and were difficult for doctors to treat. The use of these weapons created controversy, as many believed they caused unnecessary suffering and made peace harder to achieve.

"'Mass Killing' Pushed B-52 Pilot Over Brink" by George Esper, The Washington Post, January 12, 1973

This article tells the story of Captain Michael J. Heck, a U.S. Air Force B-52 pilot who refused to fly more bombing missions over Vietnam because he felt the attacks caused unnecessary destruction and suffering. Heck explained that he could no longer justify bombing civilian areas and believed the war created more evil than good. His decision made him the first American pilot to openly refuse combat missions.

Vietnam Veteran Survey

This document is the analysis of a survey conducted with 244 U.S. soldiers returning from Vietnam to understand their views on the war. Most soldiers reported that the war had mixed or negative effects on them. Many felt the South Vietnamese were more interested in survival than fighting, and nearly 40% of soldiers believed the U.S. made a serious mistake entering the war.