In 1976, America celebrated its 200th birthday during a time of national uncertainty. Just one year after the fall of Saigon and amid the Watergate scandal's aftermath, the Ford administration saw the Bicentennial as a chance to restore American pride and unity. What began as a contentious planning process became one of the most successful grassroots celebrations in American history, setting the stage for how the nation would approach its 250th anniversary in 2026.

The planning for America’s Bicentennial began on July 4, 1966, when Congress created the American Revolution Bicentennial Commission. For six and a half years, officials debated whether to hold one massive celebration in Philadelphia or Boston. After heated arguments and no agreement, Congress dissolved the commission on December 11, 1973, and created the American Revolution Bicentennial Administration (ARBA), which encouraged local communities to organize their own events instead of a centralized celebration. ARBA laid out a framework for events to be grouped into three categories – Heritage ’76 which included historically based projects and activities, Festival USA which included celebratory activities like picnics, concerts and fairs, and Horizons ’76 which focused on community development projects meant to last well beyond 1976.

ARBA’s grassroots approach proved remarkably successful. The organization reported that more than 90% of Americans participated in at least one Bicentennial-related activity. The American Freedom Train traveled 25,388 miles through the 48 contiguous states, and more than 7 million people toured its display cars. Communities across the nation organized parades, fireworks displays, historical reenactments, and patriotic festivals.

Wyoming embraced the Bicentennial with characteristic western enthusiasm. The Wyoming Bicentennial Commission (WBC) coordinated statewide celebrations. Local communities designed their own festivities including Centennial’s buffalo barbecue and turkey shoot, Thermopolis’s horse races, and the Cody Stampede, which impressed the British Broadcasting Corporation enough to send a film crew. The WBC also produced educational materials highlighting the state’s unique contributions to American history, including booklets titled “At Noon We Reached Independence Rock” (1973) and “Documents of Wyoming Heritage” (1976). Additionally, the WBC created commemorative items including a “Bicentennial Passport to Wyoming,” commemorative medallions, stamps and envelopes, and certificates of appreciation.

The celebration extended into classrooms, where Laramie junior high school teacher Daniel A. “Danny” Nelson incorporated Bicentennial themes into his history curriculum with projects like the “My America contest” and “Bicentennial youth debates.” Even corporations participated, with Montgomery Ward sponsoring Bicentennial Flag Days in communities where their stores were located and Wilbur Cross of the Continental Oil Company collecting hundreds of Bicentennial-related documents culminating in the publication of a centennial history to coincide with the national celebration.

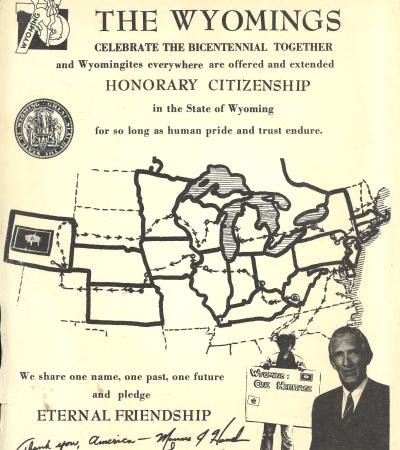

One remarkable Wyoming Bicentennial story involved twelve-year-old Manus J. Hand, who received a grant from the WBC and the Governor’s office to travel around the United States and Canada presenting honorary citizenship in Wyoming to towns, counties, and cities named “Wyoming.” This creative project demonstrated how the state used the anniversary to build connections with other communities while promoting Wyoming’s identity.

The 1976 celebration occurred during what historians call “the new nostalgia,” a cultural movement toward historical appreciation reflected in popular television shows and the landmark miniseries Roots, which author Alex Haley called his “Bicentennial present to America.” The Bicentennial era sparked the creation of numerous museums, historical societies, and preservation projects, with many public history institutions founded during the mid-1970s as a direct result of Bicentennial excitement and funding opportunities.

Not everyone embraced the official narrative, however. The People’s Bicentennial Commission, founded by Jeremy Rifkin, published “Common Sense” and organized protests challenging corporate power, including burning President Gerald Ford in effigy and disrupting official commemorations. Conservative politicians pushed back—Mississippi Senator James O. Eastland held Senate hearings titled “The Attempt to Steal the Bicentennial,” investigating the group as a security threat. Religious organizations like the National Council of Churches also offered alternative perspectives through publications like “Bicentennial Broadside.” These competing voices, preserved in collections like the Lyle and Florence Brothers papers and the Gale McGee papers at the American Heritage Center, show how the Bicentennial became a battleground for different visions of American identity.

As America approaches its 250th anniversary in 2026, the Semiquincentennial will take a different approach than 1976. The America250 initiative, established by the U.S. Semiquincentennial Commission Act of 2016, coordinates celebrations under the theme “To Form a More Perfect Union.” Unlike 1976’s focus primarily on traditional narratives, the 2026 celebration aims to “inspire our fellow Americans to reflect on our past, strengthen our love of country, and renew our commitment to the ideals of democracy through programs that educate, engage, and unite us as a nation.”

Wyoming is preparing for the Semiquincentennial through its dedicated planning website. The state’s celebration will feature year-long events including historical reenactments, parades, educational programs, and cultural exhibitions at sites like Fort Laramie National Historic Site, Independence Rock, and the Wyoming State Capitol. Plans include Native American cultural events and art installations showcasing local artists inspired by the state's history.

Looking ahead to 2076 and America’s Tricentennial, future celebrations will likely address challenges the founders never imagined, including technological transformation of democratic participation and environmental issues. The ongoing work of democracy means each generation must interpret founding principles for their own time, as reflected in the evolution from the nostalgic unity of 1976 to the inclusive accountability planned for 2026.