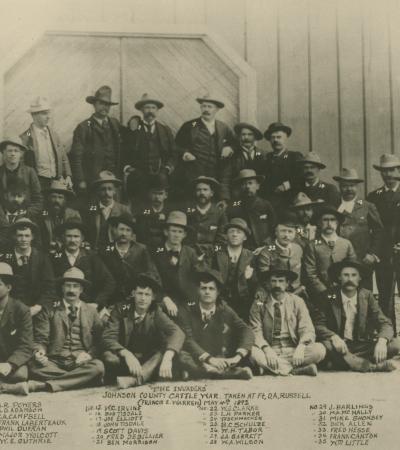

On April 5, 1892, 52 armed men rode a private, secret train north from Cheyenne. Just outside Casper, Wyo., they switched to horseback and continued north toward Buffalo, Wyo., the Johnson County seat. Their mission was to shoot or hang 70 men named on a list carried by Frank Canton, one of the leaders of this invading force.

The invaders (as they came to be known) included some of the most powerful cattlemen in Wyoming, their top employees, and 23 hired guns who were mostly recruited from Texas. The invasion resulted from long‑standing disputes between these cattle barons, who owned herds numbering in the thousands, and small operators, most running just enough cattle to support their families. The event came to be called the Johnson County War. Longtime Wyoming historian T.A. Larson ranked it “the most notorious event in the history of Wyoming.”

Numerous court records contain valuable information on the invasion, as do other government documents, especially land files. Newspaper accounts also exist, although bias is present. Two of the influential newspapers in Wyoming’s capitol of Cheyenne were owned by cattle interests. Most significantly, after the invasion--sometimes as many as 40 years later--the cattlemen and their allies published writings containing admissions that suddenly shone a bright light on contested issues. From this voluminous data, clear facts emerge from which the truth about the invasion and its causes can be determined.

The cattle barons planned, organized, and financed the invasion, declaring beforehand and afterwards that they had no choice but to take drastic action to protect their property. They said they were the victims of massive cattle stealing in Johnson County, and local authorities were doing nothing to protect their herds. They further declared, incorrectly, that Buffalo was a rogue society in which rustlers controlled everything— politics, courts, and juries. Those juries, the cattle barons said, refused to convict on cattle rustling charges no matter how strong the evidence.

Johnson County people, on the other hand, largely believed that the real reason for the invasion was the big cattlemen’s determination to drive competitors off the open range that the stockmen illegally monopolized -- to stop those who might legally take up public land under the Homestead and Desert Land acts. And Johnson County residents said that cattle rustling was greatly exaggerated, as were difficulties with prosecution for livestock crimes.

In the 1880s, the cattle barons in Johnson County and across Wyoming Territory ruled their customary ranges like private fiefdoms. Most had little concept of the true carrying capacity of those ranges, however, and overstocked them.

Cattle prices peaked in 1882, drawing more money to the business and more cattle to the land. Soon there was a beef glut. Prices began to fall, yet no one could think of anything to do but bring in even more cattle—weakening the ranges further and driving prices further down. Then bad drought in 1886 was followed by the terrible winter of 1886-1887. The Wyoming cattle industry was now in bad financial trouble and owners of the big herds deeply resented those who might challenge their unfettered right to run their cattle on public land.

Such a challenge could become deadly. That was the 1889 fate of two homesteaders, lynched near the Sweetwater River in Carbon County by six cattlemen on July 20, 1889. Ellen Watson and Jim Averell had homesteads in the middle of the cattlemen’s customary range. Sensational newspapers articles appeared immediately after the lynchings portraying Watson as a prostitute who accepted cattle for her favors. These articles, however, were written by an employee of one of the Cheyenne dailies owned by cattle barons, and recent authoritative writings show that they were false, created out of whole cloth.

That same year, 1889, Johnson County juries acquitted suspects in five cattle theft cases. Big cattlemen reacted in fury, stating publicly and in private correspondence that the acquittals proved it was impossible to present evidence to a Johnson County jury—no matter how compelling—that would produce a conviction. A close review of contemporary newspaper articles and court documents, however, shows the cases brought against the accused men to be deeply flawed, seemingly motivated by huge reward money and a frantic determination by owners of big herds to punish owners of small herds who claimed rights to grazing on public land.

In 1891, several of the cattle barons resolved to take action against their tormentors. The first step was the formation of an assassination squad of employees of the Wyoming Stock Growers Association. This small group of men included Frank Canton, a former Johnson County sheriff and a stock inspector of the association. Their first action was to hang a man from Newcastle, Wyo., Tom Waggoner, who traded horses. They followed this with an attack upon Nate Champion, a small man with a reputation as a formidable fighter. He ran a herd of about 200 cattle on one of the forks of Powder River. Champion’s stock grazed on public land, exactly as did the animals of the big cattlemen. He insisted that his cattle had as much right to grass on the public range as did the herd of any cattle baron.

Legally, Champion was absolutely right, but big cattlemen did not take well to his defiance. He was declared “king of the cattle thieves” by a newspaper reporter sympathetic to the cattle barons, although no charges had ever been brought against him. Indeed, after the invasion, Willis Van Devanter, the astute attorney for the invaders, stated there was no evidence at all to substantiate charges of cattle theft against Champion. Still, the prominent cattlemen wanted to punish Nate Champion.

In the early morning of November 1, 1891, members of the assassination squad burst into a cabin occupied by Champion and another man. The cabin was a tiny structure located next to the Middle Fork of Powder River in the Hole-in-the-Wall country about 15 miles southwest of what's now Kaycee, Wyo. Only two members of the five-man squad were able to squeeze into the cabin. Those two, however, held pistols on their two captives and demanded that Champion “give it up.” Instead, as Champion related later to The Buffalo Bulletin, he stretched, yawned, and reached under a pillow for his revolver. The shooting started at close range, but, surprisingly, Champion only received powder burns to his face. Conversely, Champion’s return fire hit its mark, wounding two men, one severely. The assassination squad fled, but not before Champion got a good look at one of them.

Private and public investigations followed, and one of the assassination squad members was forced to admit the names of all the members before two witnesses. Those two witnesses were Powder River ranchers John A. Tisdale and, perhaps, Orley “Ranger” Jones. Johnson County authorities filed attempted murder charges against Joe Elliott, the attacker identified by Nate Champion, and local newspapers pushed for charges against the wealthy and prominent cattlemen believed to be the employers of the assassination squad. A month later, on December 1, 1891, both Tisdale and Jones were assassinated. The killings created an uproar in Johnson County and the movement to charge the “higher-ups” became the whole thrust of the community.

The means to arrest and charge complicit cattlemen were at hand. If Johnson County could obtain a conviction against even one of the assassins, he would probably name his employers to avoid a long prison term. On Feb. 8, 1892, a preliminary hearing was held in the case of State v. Elliott for the attempted murder of Nate Champion.

Champion gave dramatic testimony, and Joe Elliott, who was a stock detective for the Wyoming Stock Growers Association, was bound over for trial in the district court on the attempted murder charge. Johnson County attorneys had amassed a great deal of evidence against Elliott and, with Champion’s testimony, seemed likely to convict him when his case came to trial. The big cattlemen promptly resolved, in early March 1892, to go north and invade Johnson County. The WSGA recruited twenty-three gunmen from Texas to augment the ranks of the invading stockmen.

Only a month later, the invaders left Cheyenne and traveled to Johnson County. When they arrived in the southern tip of the county, one of their local spies told them that “rustlers,” including Champion himself, were holed up in a cabin at the KC Ranch, just a few miles north.

The invading cattlemen knew that with Champion’s testimony Johnson County had a strong case against Elliott, and upon Elliott’s conviction the trail would lead back to his employers. If Champion was not killed, these invaders would probably land in the penitentiary. After long argument the invaders took a vote. The decision was made to go to the KC Ranch and kill him.

They surrounded Champion. For hours he fought the 50 men, wounding three. Finally, during the middle of the afternoon of April 9, 1892, the invaders torched the cabin, forcing him out and shooting him down.

By then, however, the countryside had been alerted, and men all over the area rushed to confront the invaders. The invaders holed up south of Buffalo at the T. A. Ranch. There, they were surrounded by local citizens—a posse that eventually grew to more than 400 men. The posse conducted a formal siege, no doubt led by the Civil War veterans among them.

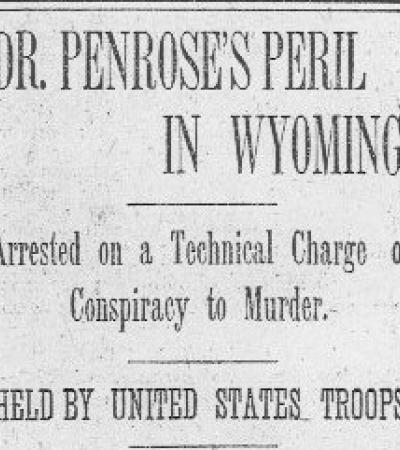

Over three days the posse slowly closed in on the invaders. On the morning of the third day, 14 posse members started moving toward the T. A. Ranch house, using a ponderous, movable fort called a “go-devil” or “ark of safety” made of logs on the running gears of two wagons. The idea was that when the posse got close to the invaders’ fortifications, they would use dynamite to force the invaders out into the open. The running gears came from the captured supply wagons of the invaders, which contained dynamite intended for use against the people of Johnson County. But the posse never got the chance to use its new weapon. In the nick of time, troops of the Sixth U.S. Cavalry from nearby Fort McKinney rode onto the scene and escorted the invaders to Fort D. A. Russell near Cheyenne to await trial.

Wyoming Governor Amos Barber had summoned the soldiers. According to accounts written years later by the invaders and their sympathizers, Barber was thoroughly knowledgeable about and supportive of the invasion. When he learned that his cattlemen friends were in deep trouble, he telegraphed President Benjamin Harrison in Washington, D. C. When the telegrams, for reasons that are unclear, failed to go through, Barber had asked the two senators from Wyoming, Joseph Carey and Francis Warren, to go to the White House and pay a personal call on the president. Harrison was quickly convinced that there was an “insurrection,” as Barber’s first telegram had termed it, in Wyoming and agreed to call on the Sixth Cavalry to suppress it.

Once the invaders were taken into custody, however, Governor Barber assumed control over them and refused to even allow them to be questioned; the governor completely frustrated the investigation and prosecution of the invaders by Johnson County authorities. Indeed, Johnson County had to foot the bill to feed and house the prisoners, not to mention the substantial charges for preparation and presentation of the criminal cases. The state provided no financial assistance whatever.

The invasion left Northern Wyoming emotionally charged with residents even more violently opposed to the cattle interests. On June 13, 1892, the Ninth Cavalry rode into the situation; it was one of four black units then in the regular army. The Ninth established Camp Bettens on the Powder River in eastern Sheridan County. Their arrival followed correspondence to U.S. Senator Joseph M. Carey by the invaders and their allies including invasion leader Frank Wolcott. It appears that the invaders attempted to use to their advantage racial hostility they believed existed between the black cavalrymen and the Texan mercenaries. Soon after the Ninth arrived, they were harassed by residents of the nearby settlement of Suggs, a rough and tumble end-of-tracks town on the Burlington Railroad where prostitution, gambling, and liquor seem to have been the main attractions. Tensions rose when a soldier was insulted by a town resident in a saloon resulting in retaliatory action by fellow soldiers who rode into town and exchanged fire with residents. One soldier was killed. The army appears to have buried the incident quickly to prevent Suggs from becoming a major public issue. Both white and black infantrymen were sent to Coeur d'Alene, Idaho, less than one month after the shooting.

As for the invaders, they were released on bail and told to return to Wyoming for the trial. However, many fled to Texas and were never seen again. In the end, the invaders went free after the charges were dropped, the excuse being that Johnson County refused to pay for the costs of prosecution. In reality, sparsely populated Johnson County could not afford the cost of housing the men at Fort D.A. Russell; costs were said to exceed $18,000.

The cattle barons had been protected by a friendly judicial system, but that system could not protect the political figures involved from Wyoming voters. The Republican Party was closely associated with the cattlemen and their principal organization, the Wyoming Stock Growers Association. The 1892 election was a landslide in favor of the Wyoming Democratic Party. A Democrat was elected governor, and another was elected to the U.S. Congress. At the time, U.S. senators were still elected by state legislatures; enough Democrats were elected to the Wyoming state legislature that no Republican could be selected for the U.S. Senate. Republican Senator Francis E. Warren lost his seat.

Permanent and positive changes occurred in response to the Johnson County War. Wyoming people had made it abundantly clear—by their votes and by strong resolutions to public officials reported in newspapers-- that they would not tolerate abuses like the invasion of Johnson County. Significantly, the organization primarily responsible for the Johnson County War, the Wyoming Stock Growers Association, was changed forever. Plagued by continuing economic woes, the cattle barons in the association permanently altered this organization in 1893 when they opened their group to all the stock growers in Wyoming.

In what was a galling but necessary action, the small cattlemen of Wyoming, vilified such a short while before, were invited to join. This action abruptly halted the overwhelming hostility of the big cattlemen toward the smaller operators and stopped such programs as the confiscation, at point of sale, of suspected rustlers’ cattle by the Wyoming Livestock Commission.

After 1893, a measure of peace descended upon the Wyoming range, although it wasn’t until 16 years later that armed economic vigilantism was finally stopped in Wyoming. Cattlemen raiders —killing sheep and sheepherders—were convicted of serious crimes after the 1909 Spring Creek Raid south of Tensleep, Wyo., and were sent to the Wyoming penitentiary. Wyomingites could finally claim to have put frontier mob rule behind them.

Many thanks to John W. Davis and WyoHistory.org for much of the text contained in this article.