Vertical files and other materials related to the Rock Springs Massacre and the Chinese experience in Wyoming. Vertical files contain items such as news clippings, booklets, photographs, pamphlets, reports, and more. The materials are typically loose, separate pieces organized in folders and arranged by subject. The name comes from how they are stored: vertically in filing cabinets.

"The Chinese Question: A Paper Read Before the Berkeley Club," by John H. Boalt, August 1877

This essay by California mining attorney John H. Boalt (1837-1901) is credited as launching the campaign for the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 which banned immigration of Chinese laborers to the United Stated. In the essay he wrote that the Chinese were unassimilable liars, murderers and misogynists who provoked "unconquerable repulsion."

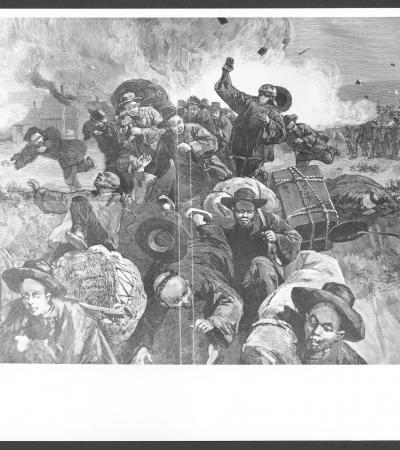

Harper's Weekly illustration of Rock Springs Massacre, 1885

"The Massacre of the Chinese at Rock Springs, Wyoming" drawn by Thure de Thulstrup from photographs by Lieutenant C.A. Booth, Seventh United States Infantry.

View of route used by Chinese escaping the Rock Springs Massacre

Some of the Chinese miners fled the 1885 riot through steep bluffs outside Rock Spring and out into the hills beyond. A number of them then followed the railroad line to Green River located 14 miles away. The railroad line would have been easy to find since mining was done close to the line during this time period. U.P. trainmen rescued them as they fled along the tracks.

Another view of route used by Chinese escaping the Rock Springs Massacre

Chinese quarters in Rock Springs, ca. 1890

During the 1885 riot, almost 80 cabins housing Chinese miners were burned.

Miners' cabins in Rock Springs along Bitter Creek, ca. 1900

Because their families were not with them, the Chinese miners, along with many other miners, tolerated rough living conditions. Many of the Chinese miners lived eight or nine to a room to save on rent.

Home of bachelor coal miner built of rock and dirt, undated

Two houses of miners, September 1920

Although taken in 1920, miners' home were much the same for many years.

Housing for Union Pacific Coal Company officials, ca. 1900

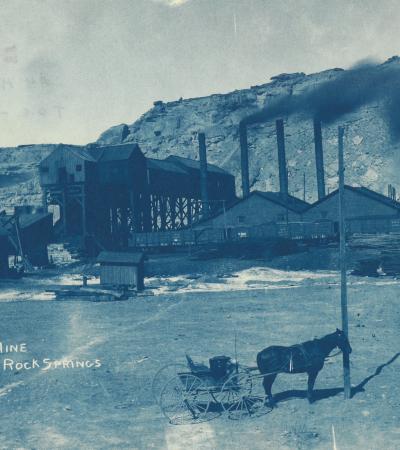

Coal mine No. 4, Rock Springs, ca. 1890

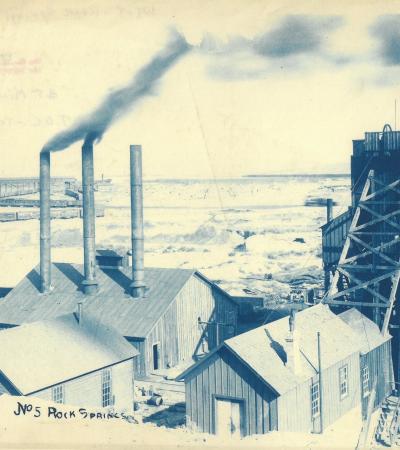

Coal mine No. 5, Rock Springs, ca. 1890

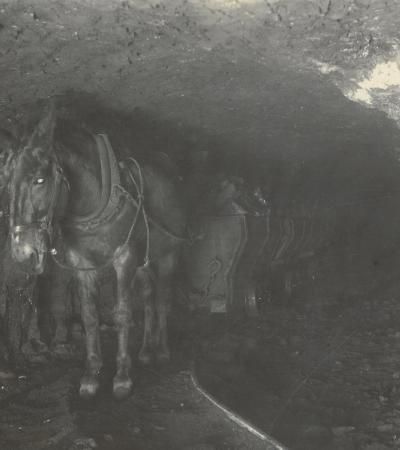

Mule hauling coal out of Rock Springs coal mine, undated

Mining teams used hand picks to chip out narrow horizontal channels at the base of the coal seams and then drilled holes into the seams and inserted tubes of black powder. The fuses were lit, the powder exploded, and chunks of coal dropped. The coal was then loaded into cars, pulled to the entry shaft by mules, and lifted up the shaft to the surface for weighing and transfer to railroad flats.

View of cave-in of underground Union Pacific coal mine, Rock Springs, 1930s

Underground coal mining was quite hazardous in the 19th and early 20th centuries. There were periodic cave-ins, coal dust that harmed the respiratory system, and carbon monoxide poisoning from lack of ventilation. There were also gas explosions, fires, and floods to contend with.

Another view of cave-in of underground Union Pacific coal mine, Rock Springs, 1930s

Early coal mines used the room-and pillar excavation method. Pairs of men created long narrow rooms at right angles to the mine tunnels as they removed the coal. The rooms were about 24 feet in width and hundreds of feet long. The walls separating the rooms were the pillars that supported the roof of the mine and the pillars were supplemented with timber posts to prevent cave-ins.

Joss House, Evanston, Wyoming, ca. 1890

An old name in English for Chinese traditional temples is "joss house". "Joss" is an Anglicized spelling of deus, the Portuguese word for "god". The term "joss house" was in common use in English in the nineteenth century. It was constructed in 1874.

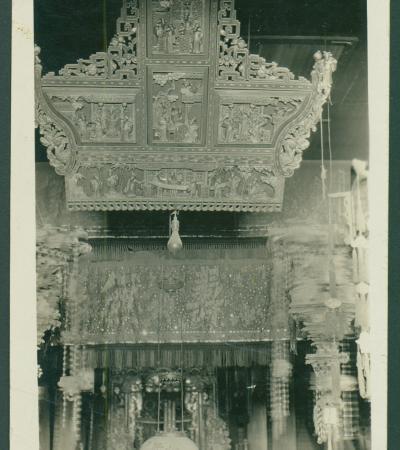

Joss House upper section of altar, Evanston, Wyoming, ca. 1890

At the time, only three Joss Houses existed in the United States: one in San Francisco, one in New York City and one in Evanston, Wyoming.

Joss House lower section of altar, Evanston, Wyoming, ca. 1890

Article in unnamed newspaper reporting the death of Ah Say, 1899

AH Say became superintendent of the Chinese UPRR workers and a recruiter of sorts, traveling to California and Omaha to recruit and escort new Chinese workers to Southeast Wyoming, contracting with both the Central Pacific and Union Pacific Railroads. By the time of his death, the Emperor of China had also appointed him a consul. He also became a naturalized citizen and assimilated into Rock Springs society, while honoring his own cultural heritage.

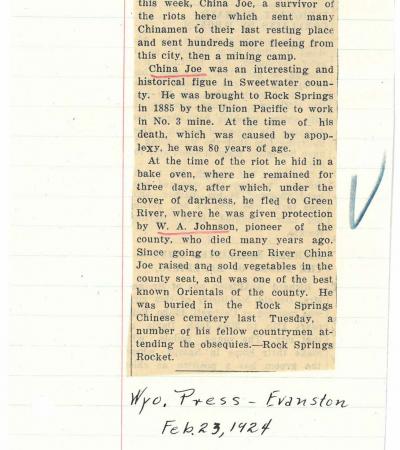

Newspaper clipping on death of "China Joe," Wyoming Press (Evanston), February 23, 1924

The Wyoming Press in Evanston, Wyoming, notes in this death notice that "China Joe" was a survivor of the riot in Rock Springs and hid until he could escape to Green River, located 14 miles from Rock Springs. China Joe then remained in Green River.

Chinese miners aboard ship in San Francisco, California, to begin their trip home to China, 1925

Photo caption: "From George Pryde, Rock Springs, Wyo. Chinese from Rock Springs ready to sail for home for old home in China after being in Rock Springs for 40 years, November 1925." George Pryde was an executive with the Union Pacific Coal Company.

Chinese miners before their return to China, 1926

Photo caption: "Nine 'Old Timers' (Chinamen) sent home to their native land after 40+ years of service in mines of the Union Pacific Coal Company." The caption was written by University of Wyoming Professor and Wyoming historian Grace Raymond Hebard.

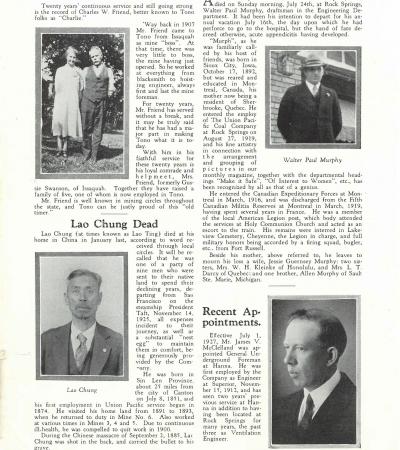

"Lao Chung Dead," Employes' Magazine, Union Pacific Coal Company, September 1927

Lao Chung who had returned to China in November 1925 died January 1, 1927. The article states that Lao Chung was shot in the back during the 1885 riot and "carried the bullet to his grave."

"Joe Bow Marries in China," Employes' Magazine, Union Pacific Coal Company, November 1927

Joe Bow sent a photograph of himself, his new wife and her son to the magazine. Bow was one of the longtime Union Pacific miners who returned to China.

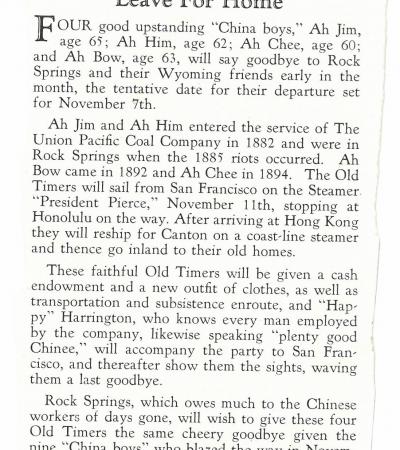

"Four More of Our 'China Boys' Leave for Home," Employes' Magazine, Union Pacific Coal Company, November 1927

Article explaining that Ah Jin, Ah Him, Ah Chee, and Ah Bow are returning to China. Article explains that Ah Jin and Ah Him were employed by Union Pacific during the Rock Springs Massacre.

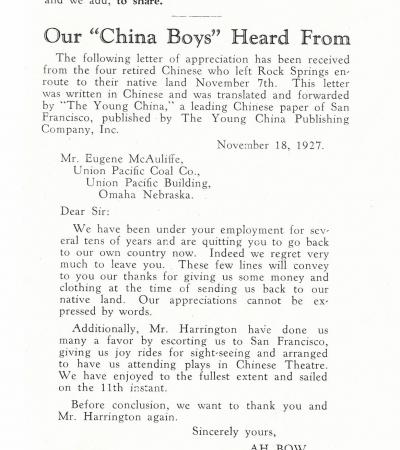

"Our 'China Boys' Heard From," Employes' Magazine, Union Pacific Coal Company, November 1927

Article with a transcription of a note to the Union Pacific Coal Company from Ah Jin, Ah Him, Ah Chee, and Ah Bow regarding their return to China.

"Homeward Bound" by Frank Tallmire and H.J. Harrington, Employes' Magazine, Union Pacific Coal Company, December 1927

Another article regarding Ah Him, Ah Jin, Ah Chee, and Ah Bow and their request to return to China. Union Pacific provided the men with clothing, a farewell banquet, a traveling clock, and travel arrangements.

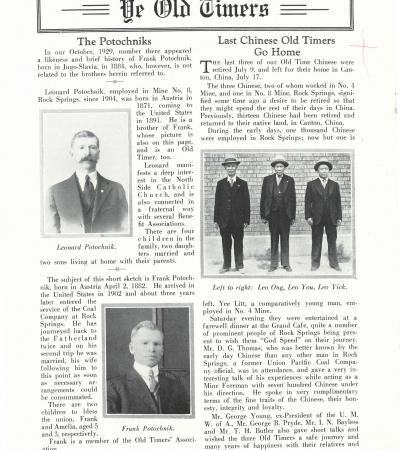

"Farewell Banquet for Lao Chee," Ye Old Timers series, Employes' Magazine, Employes' Magazine, Union Pacific Coal Company, October 1929

Also known as "Jim," Lao Chee also chose to return to China after more than 40 years of employment by Union Pacific. He had arrived in Rock Springs in 1880, five years before the riot.

"Last Chinese Old Timers Go Home," Ye Old Timers series, Employes' Magazine, Employes' Magazine, Union Pacific Coal Company, August 1932

Article noting the return to China of Leo Ong, Leo You, and Leo Yick.