Watercolor artist Estelle Peck Ishigo (1899-1990) was interned with her Japanese American husband Arthur Ishigo at Heart Mountain. After the Pearl Harbor attack, both she and her husband lost their jobs. Arthur was ordered to be interned and Estelle followed him although she was Caucasian and not forced to do so. Her papers contain photographs and sketches she created during her time at Heart Mountain.

Additional content for this collection can be found in the "Inventory for Collection."

Estelle Ishigo at Heart Mountain Relocation Center, 1944

Estelle shown near a barracks building.

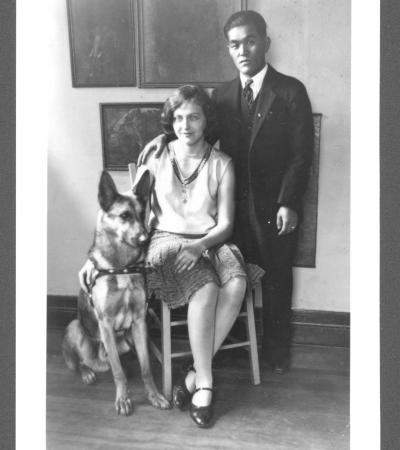

Estelle Peck and Arthur Ishigo, ca. 1928

Estelle married San Francisco Nisei Arthur Ishigo in 1928. They married in Mexico to avoid American anti-miscegenation laws.

Estelle Ishigo outside her trailer home after release from Heart Mountain Relocation Center, ca. 1945

After the war and their release from internment, Arthur and Estelle lived in poverty for many years. Arthur died in 1957.

Arthur Ishigo shoveling coal at Heart Mountain Relocation Center, ca. 1944

Arthur worked in a boiler room that provided hot water for a block of barracks.

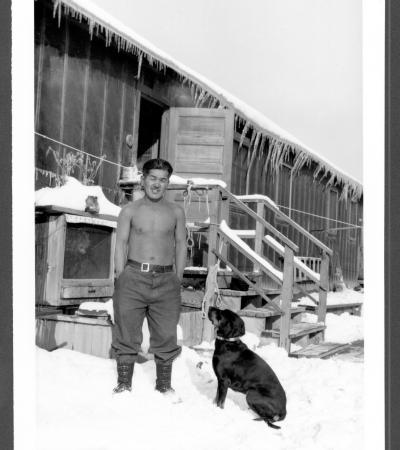

Arthur Ishigo, ca. 1944

Arthur Ishigo standing by packing cases with dog near hut B-14-6.

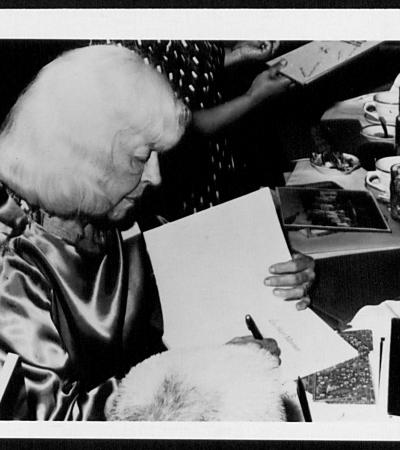

Estelle Ishigo signing copy of Lone Heart Mountain, ca. 1972

After the war and their release from internment, fellow Heart Mountain inmates helped Ishigo republish her 1972 book Lone Heart Mountain. Estelle died on February 25, 1990, in Los Angeles, California.

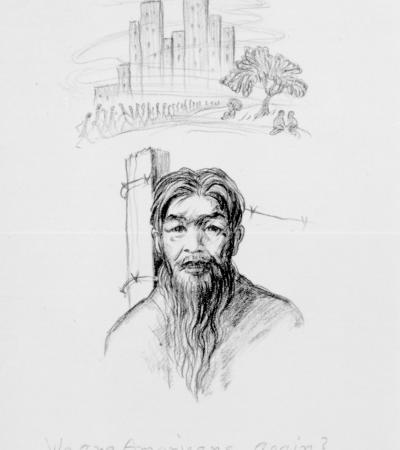

Sketch by Estelle Ishigo titled "We Are America, Again?"

Executive Order 9066 was rescinded in December 1944. Internees were released, often to resettlement facilities and temporary housing. Interned Japanese-Americans had not only lost their personal liberties, many also lost their homes, businesses, property, and savings.

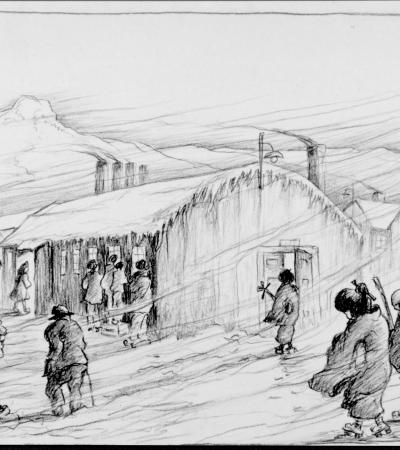

Sketch by Estelle Ishigo of Heart Mountain Relocation Center internees braving a snowstorm, ca. 1944

Internees braved the elements to travel between buildings during their everyday life.

Sketch by Estelle Ishigo of rationing coal for apartment stoves at Heart Mountain Relocation Center, ca. 1944

It took about four train car loads of coal a day to provide heat for internees during the cold winter months.

Sketch by Estelle Ishigo of young boy sitting by a hut, ca. 1944

Although there were some activities for children at the center, young children had days of boredom and loneliness.

Sketch by Estelle Ishigo of boys rescuing a kite from barbed wire, ca. 1944

Playtime could often become dangerous near the barbed wire fence.

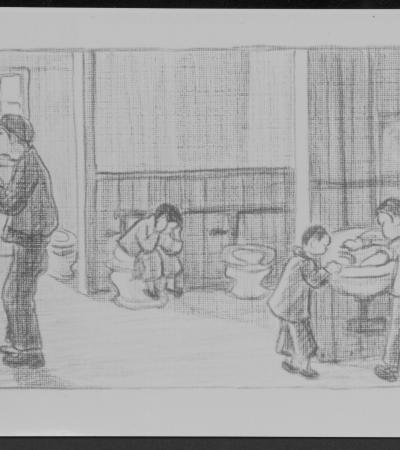

Sketch by Estelle Ishigo of men's washroom at Heart Mountain Relocation Center, ca. 1944

Men's and women's washrooms offered little if any privacy.

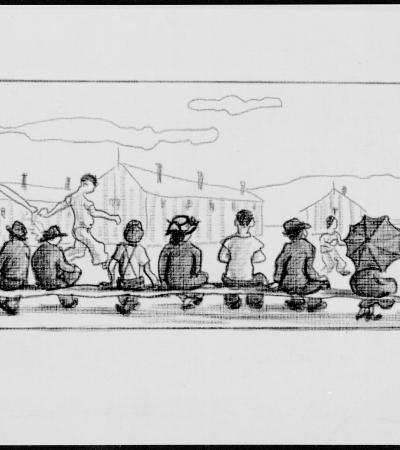

Sketch by Estelle Ishigo of young male internees playing baseball, ca. 1944

Internees did what they could to make their situation liveable such as sports, clubs, and events.

Sketch by Estelle Ishigo of family life in Heart Mountain Relocation Center barracks apartment, ca. 1944

Families lived in apartments within tarpapered barracks. The largest apartments were simply single rooms measuring 24 feet by 20 feet.

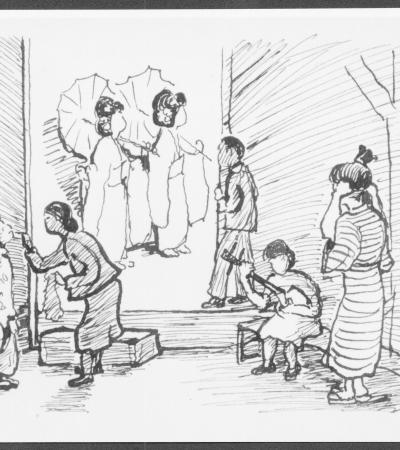

Sketch by Estelle Ishigo of amateur theatrical geisha, ca. 1944

In Japan, geisha is a class of female performance artists trained in traditional performing arts styles, such as dance, music and singing,

Sketch by Estelle Ishigo of adults attending evening school, ca. 1944

Adults attended evening school for classes in such things as sewing, English, and the U.S. Constitution.

Sketch by Estelle Ishigo of young boys loitering around a warming stove, ca. 1944

In many cases doors and windows were improperly installed and failed to close completely. In addition, gaping cracks between wallboards made both privacy and protection from Wyoming weather difficult. Coal burning stoves became a main heat source during the cold winter months.

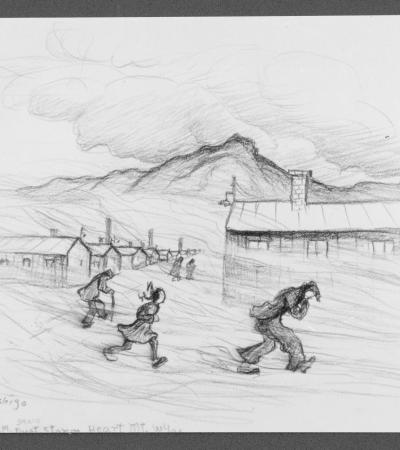

Sketch by Estelle Ishigo of internees caught in a dust storm, September 4, 1942 at 4:30 PM.

Internees braved the elements to travel between buildings during their everyday life.

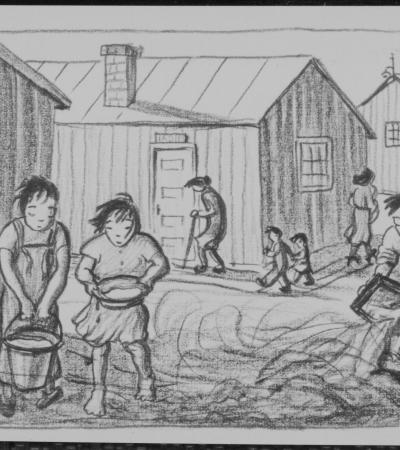

Sketch by Estelle Ishigo of children dumping dirty water from laundry, ca. 1944

Almost half of the Japanese Americans interned nationally were children. They had to help with daily tasks and chores at internment centers like Heart Mountain.

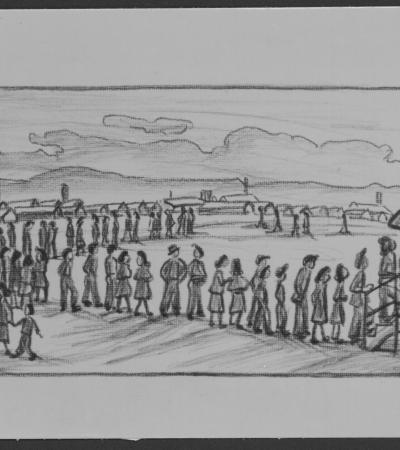

Sketch by Estelle Ishigo of mess hall line, ca. 1944

Internees had to wait their turn to eat at the mess hall despite harsh weather conditions.

Sketch by Estelle Ishigo of serving food in mess hall, ca. 1944

Inexpensive foods such as wieners, dried fish, pancakes, macaroni, and pickled vegetables were served often. But internees were able to supplement their diet by completing a 5,000-foot irrigation canal and clearing many acres of sagebrush to make way for peas, beans, cabbage, carrots, cantaloupe, watermelon, and other fruits and vegetables. Milk was supplied through a creamery in Powell, but the camp raised cattle, hogs and chickens for its own consumption.

Sketch by Estelle Ishigo of internees putting out a fire, ca. 1944

Fires were common at Heart Mountain because of the tar papered covered barracks.

Sketch by Estelle Ishigo of meeting at Heart Mountain Relocation Center, ca. 1944

The center was known for fomenting and supporting draft resistance amongst the Nisei during World War II through the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee. There existed at Heart Mountain a tradition of protest, both violent and non-violent.

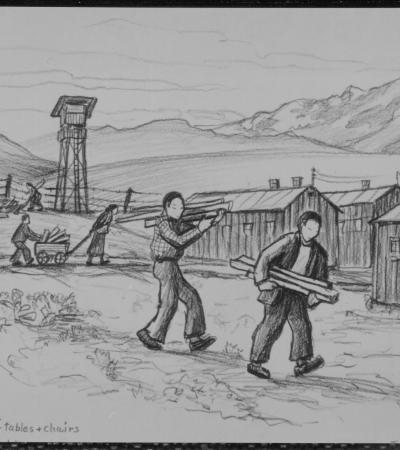

Sketch by Estelle Ishigo of adults scavenging wood for tables and chairs, September 26, 1942

Furniture making was the most immediate art activity of many detainees during the first days of imprisonment as they attempted to transform dilapidated barracks into adequate shelter.

Sketch by Estelle Ishigo titled "Relocation, another move," 1945

Only 2,000 people had left Heart Mountain by June 1945. Those who left were only given $25 and a train ticket to the destination of his or her choice. If the internee didn't supply officials with a home address, the person was simply sent to the area where they resided prior to the war, whether they had a home there or not. Wyoming officials discouraged Japanese Americans from remaining in the state and earlier had passed laws preventing them from owning land and from voting. The last trainload of incarcerees left Heart Mountain on November 10, 1945.